I’ve had a lot of fishing journal false starts. For a month at a time, maybe two, between the ages of 16 and 25, I’d diligently log every detail about each trip to the striper surf or trout stream. Weather, wind, and water temperature data all neatly recorded. Most of the time, I did this in a cheap marble notebook, but there were a few rounds of rekindled journaling enthusiasm inspired by the purchase of a sexier hardbound book. By the time I bequeathed it to my son, it would be worn and tattered, brimming with sage advice. Thank God the kid will have the “Sage Fishing Advice App” to fall back on, because even the promise of an invaluable heirloom couldn’t keep me committed.

The funny thing is, every fisherman knows that well-kept journals are one of the best damn tools in your arsenal. Countless world-renowned anglers have reiterated this to me over the years. Yet, despite this being pounded into our heads, most of my close fishing buds don’t keep logs or, like me, vehemently took pen to paper for a few pages and then trailed off. The exception is my good friend Mike Sudal, who’s taken fishing journals to a level that most of us will never attain, but we can learn from, and perhaps use to re-spark our fires for record keeping.

Sudal is a passionate, well-traveled angler, but he’s also an artist with chops that have landed his work in the Wall Street Journal, Salt Water Sportsman, Field & Stream, and Outdoor Life, among many other publications. Since he was 13 growing up in Northeast Pennsylvania, Sudal has kept detailed fishing journals. For many years, they were pretty standard; conditions, lure and fly choices, results. But as Sudal grew as an artist, his journals became more visual. Instead of recording every single trip in written form, his journals became scrapbooks of particularly memorable fish or situations that he wanted to remember, often because what he learned during that moment in time couldn’t be captured in numbers but would prove valuable during later outings.

You could spend hours leafing through Sudal’s years of journals, but I challenged him to pick the six entries that are most meaningful to him.

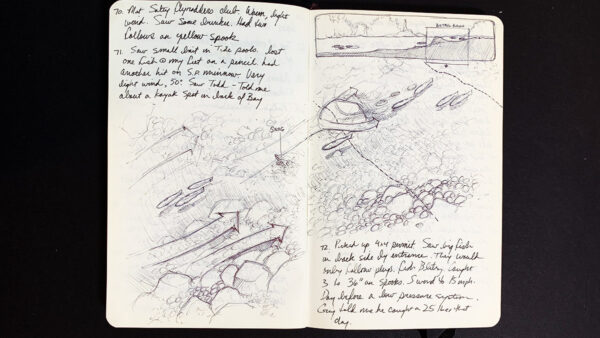

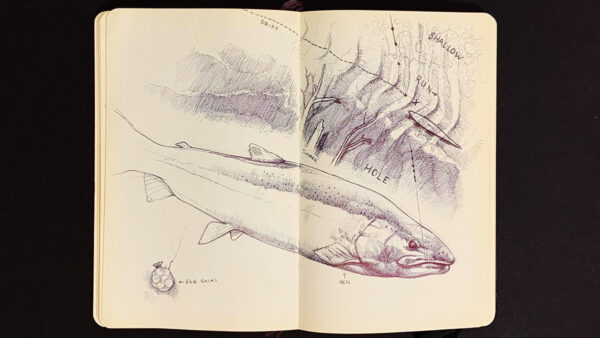

“Steel Run”- Pulaski, New York, 2011

Sudal whipped up this scene from New York’s Salmon River in 15 minutes, not long after returning home from the trip. The fishing was so good, he wanted to record the details before he forgot any of them. But this cross section of a steelhead run is indictive of the way Sudal thinks when he’s fishing.

“I’m always trying to visualize what’s going on underwater,” he said. “That’s why a lot of my journal entries sort of map out what I think unfolded below the surface. The steelhead were absolutely stacked in this one little area within this run. But to catch them, you had to get your drift exactly right.”

What’s not so evident in the sketch is how the information Sudal recorded correlates to timing. He says the trick was having your fly bouncing on the bottom everywhere between the dotted lines. If you hit bottom too late, you weren’t getting a strike; too early and you were in that snag drawn in ahead of the boulder, which Sudal says, “cost me about two dozen damned flies.”

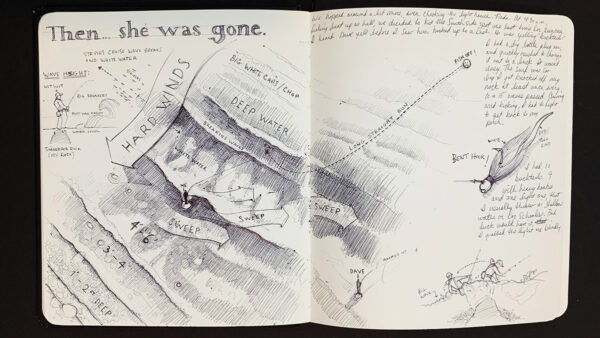

“Then…She Was Gone” – Montauk, New York, 2014

“The weekend before I drew this, I’d lost a really big striper in the Cape Cod Canal,” Sudal said. “Then it happened again on this trip the following weekend in Montauk during one of those nights that really beat you up.”

Sudal and his friend, Dave Holler, were wet-suiting during a fierce northeast blow that sent occasional chest-high breakers rolling in to knock them off their rocks all night. Just before sunup, Sudal hooked into a fish he couldn’t stop. After a blistering run, he felt a sharp pop and reeled in a bucktail with a bent-out hook.

“I learned a tough lesson that night,” he said. “I’d been throwing heavy bucktails with stronger hooks, but I wasn’t getting any big fish on them. I had one smaller, lighter bucktail, so I switched. I found out that I could sort of let the lighter one hold in the wave without retrieving it, so I was just sort of letting it hang out there in the current. Of course, that’s what got the big fish, but unfortunately the lure couldn’t handle it.”

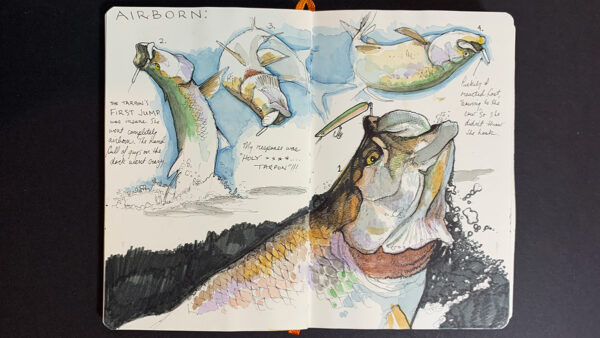

“Airborn” – Islamorada, Florida, 2015

Sudal was only goofing around before dinner. He walked to the end of the dock behind his Florida Keys hotel with a fairly light surf outfit. All he was hoping for was a barracuda, and considering they’re not the most finicky fish, he didn’t even bother rigging up a proper leader; he tied a pencil popper directly to his 50-pound braid. Within a few retrieves, as he burned the lure across the surface, a big tail broke the water behind the pencil and disappeared. The tail did not belong to a ’cuda.

“At first I didn’t know what it was, so I paused, then slowed the retrieve to a walk-the-dog,” Sudal said. “As I’m walking, I give the lure one hard snap and it gets engulfed. As soon as I set the hook, this 65-pound tarpon goes airborne and I can see it’s just the rear hook of the pencil in the tip of its top lip.”

The plan was to enjoy the fight for as long as it lasted, as Sudal assumed there was no way he’d land this fish. But the battle attracted a crowd, and with the help of some fellow anglers, 30 minutes later he brought the tarpon to hand. “The funny thing was, a pencil popper is a Northeast lure I brought from home,” he said. “There were probably five for sale in the closest tackle shop and they must have been bought out, because the next night, all the guys that helped me were on that dock throwing one.”

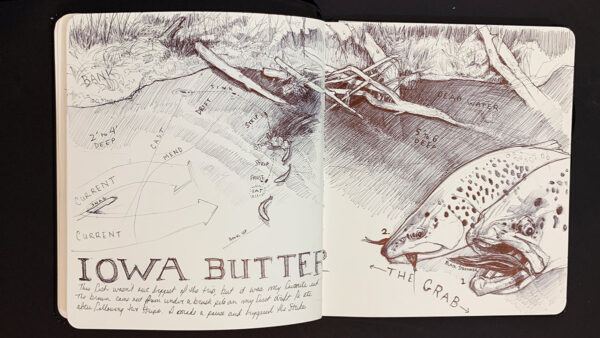

“Iowa Butter” – Decorah, Iowa, 2018

This entry is special to me, because I was looking over Sudal’s shoulder when the deal went down on Waterloo Creek in the Driftless Region of Iowa. Thanks to a week of rain prior to our visit, most of the bigger rivers we intended to fish were blown out. Our friend and local trout ace, Dave Strom, wasn’t a fan of Waterloo Creek, but it was the only piece of trout water running clear, so we gave it a shot. When this particular brown pounced on Sudal’s streamer, it was like a pressure release valve opening. After days of hitting log jams and undercurrent banks on a few streams that were kind of fishable but produced no fish, we needed this one.

“We had such a black cloud over us in Iowa,” Sudal said. “Then I remember walking up on this spot. I looked at the log jam and said, ‘there’s a big brown in there. I know it.’ Nobody had hit this hole yet either, so I was getting first crack. I didn’t like my first cast, but the second was perfect. That black streamer swung right in front of the wood. I gave it a pause, and that fish came out and rammed it. From that point on, I felt dialed in, like the black cloud lifted.”

And it did. It’s funny how it only takes that one fish to turn everything around. For the rest of that day, we moved or hooked a brown in pretty much every place we thought one should be. Sudal has gotten plenty of similar textbook eats since, but the backstory and the struggle are what made this one worthy of logging.

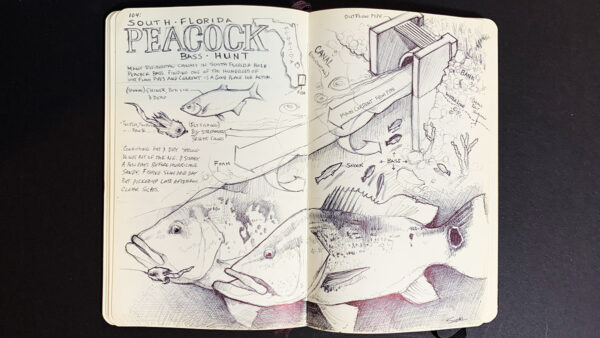

“South Florida Peacock Bass Hunt” – Fort Lauderdale, Florida, 2015

“Peacock bass were a bucket list fish for me,” Sudal said. “So, on a trip to Fort Lauderdale, I had to take a shot. But I didn’t have a boat or a guide, so I did a bunch of research to figure out where to fish. My buddy and I ended up at a canal, and we started catching little ones right away. Then we came across the outflow I diagrammed in my journal.”

On Sudal’s first cast with a streamer, a big peacock rushed the fly but missed. After it disappeared back into the depths, he told his buddy to drop a live shiner and the fish hammered it. The duo ended up scoring a few more large peacocks, but the drawing illustrates the real magic of South Florida backwater canals; each outflow creates a mini ecosystem and you never know what’s lurking below.

“We caught a few largemouth and gar, but we kept hearing these massive pops toward the back of the outflow,” Sudal said. “Next thing I know, this dude pulls up in a truck and we start talking. He told me what I heard popping were big snook. I ditched the peacock pursuit and started focusing on the those, but I couldn’t get one to eat. But it was fascinating to me how the different fish hold in such specific locations in one tiny area. The peacocks were right below the pipe in the flow. The largemouths held off to the side, and the snook patrolled the foam line in the back.”

“Pinning Steel” – Pulaski, New York, 2012

There may not be as much going on in this illustration compared to others in Sudal’s journals, but these pages commemorate a revelation for the steelhead junky. It was January and bitterly cold, but not wanting to waste a few days off, he took the five-hour drive to New York’s Salmon River. What he found after that drive was a raging torrent of dirty water, making it practically impossible to be effective with his fly rod. Luckily, he bumped into an old buddy from Pennsylvania that happened to be fluent in centerpin fishing.

“He knew I was struggling, so he handed me his pinning rod,” Sudal said. “But I’d never used one before. I had no idea what to do with it, so he spent about 20 minutes teaching me the basics. I caught on quick I guess, got the feel for it just enough, and we spanked steelhead on centerpin the rest of the day. I went out shortly after that trip and bought a pinning outfit.”

Sudal prefers to catch his steel on the fly, but the lesson from that chance encounter is that you have to have a variety of tools in your toolbox. He never makes a run to the Salmon River without a pinning rig, because it makes blow-out conditions not only fishable, but productive since a centerpin presentation allows for extremely long drifts that cover far more water than you could with a fly even under normal flow conditions.

A few days after chatting with Sudal, I got an unsolicited fishing rod in the mail. The company was hoping I’d weigh in on this advanced stick that transmits data like weather, location, number of casts, and fish caught to your phone via Bluetooth connection. On one hand, I have to marvel at the technology, and it’s hard to deny that gadgetry like this could, in fact, help anglers catch more fish by auto-logging data.

As the years press on, it’s likely we’re going to see more of our fishing gear capable of transmitting a Wi-Fi signal, and maybe the infusion of technology and fishing gear will make our kids better anglers than we ever hoped to be. But whether I choose to play around with the rod or not, it has an internal battery life of two years, according to the company. I won’t likely be handing it, or the files from a phone that will be antiquated, to my kids when they’re ready to head to the water on their own. Sudal’s journals, on the other hand, are destined to be passed from generation to generation in his family, whether his kids, grandkids, and beyond use them to slay more fish or not.

All images courtesy of Mike Sudal.

Conversation